The abdominal skin is loosely attached to underlying structures except at the umbilicus, where it is firmly adherent.

Langer's lines are lines of tension based on the orientation of dermal fibers in the skin.

On the anterior abdominal wall, these lines are arranged mostly in a transverse fashion.

As a consequence, vertical incisions heal under more tension and therefore have a propensity to develop into wider scars.

This is more noticeable in those patients who tend to form keloids.

Conversely, transverse incisions, like a Pfannenstiel, heal with a much better cosmetic appearance.

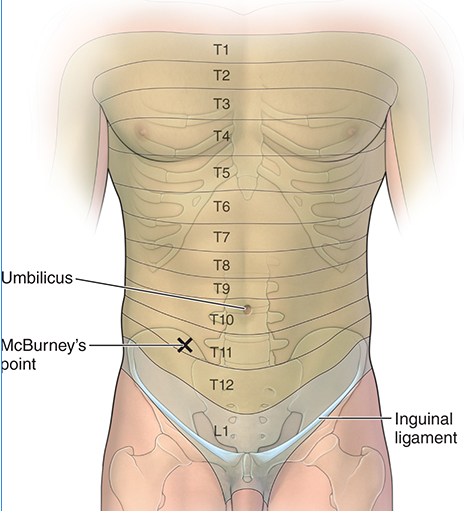

The skin receives its vascular supply via the intercostal and lumbar vessels and its segmental innervation via the ventral rami of the intercostal and lumbar spinal nerves.

The subcutaneous layer can be separated into a superficial, predominantly fatty layer known as Camper fascia, and a deeper dense collagenous connective tissue layer known as Scarpa fascia.

Camper fascia continues onto the perineum to provide fatty substance to the mons pubis and labia majora and then to blend with the fat of the ischioanal fossa.

In contrast, Scarpa's fascia continues into the perineum, but the nomenclature is changed relative to the region in which it is located. For example, Scarpa's fascia becomes Colles' fascia when surrounding the roots of the penis and clitoris; it becomes superficial penile (or clitoral) fascia when it surrounds the shaft of the penis (or clitoris); and it becomes dartos fascia in the scrotum.

As a result, perineal infection or hemorrhage superficial to Colles fascia has the ability to extend upward to involve the superficial layers of the abdominal wall.

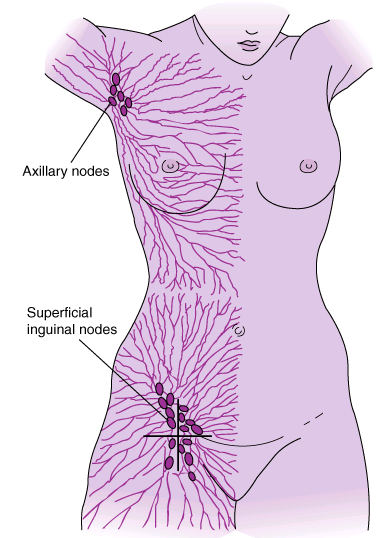

Embedded in the adipose tissue of Camper's fascia are the superficial epigastric veins, which drain the anterior abdominal wall. These cutaneous veins drain into the femoral and paraumbilical veins.

Camper fascia and Scarpa fascia firmly attached to midline aponeuroses and to the fascia lata.

A patient diagnosed with cirrhosis (fibrotic scarring) of the liver may present with portal hypertension. Blood pressure within the portal vein increases because of the inability of blood to filter through the diseased (cirrhotic) liver. In an attempt to return blood to the heart, small collateral (paraumbilical veins) veins expand at and around the obliterated umbilical vein to bypass the hepatic portal system. These paraumbilical veins form tributaries with the veins of the anterior abdominal wall, forming a portal–caval anastomosis, and drain into the femoral or axillary veins. In patients with chronic cirrhosis, the paraumbilical veins on the anterior abdominal wall may swell and distend as they radiate from the umbilicus and are termed caput medusae because the veins appear similar to the head of the Medusa from Greek mythology.